The Challenge: When People Haven't Yet Imagined the Possibilities

Innovation teams face a fundamental challenge that goes beyond technical feasibility: users can't give meaningful feedback on experiences they haven't integrated into their lives. Sometimes the technology doesn't exist yet—but often it does exist, and people simply haven't discovered how it fits into the way they work or live. They're unfamiliar with the possibilities, unable to articulate needs they don't yet know they have.

Traditional prototyping validates solutions at the end of projects—when changing course is most expensive. Traditional design thinking prototypes explore ideas collaboratively—but stay within familiar frameworks that don't challenge assumptions. Meanwhile, stakeholders jump to early decisions based on their own biases, and once a problem is framed, it becomes extraordinarily difficult to change the outcome. Sometimes the ego of people in power extends these biases as long as possible, even when most people quietly recognize it's the wrong approach.

The question driving this research: How do you help people discover meaningful relationships with technology they haven't yet imagined using?

"Technology cannot be pushed to people under the assumption that they're motivated to use it. Especially now with the rise of AI, the main problem is becoming adoption after the novelty and hype. Understanding motivation and cultural values is the key to designing technology in ways that people feel connected to their priorities—finding positive meaning each time they use it."

This approach of provocation is essential with emerging technologies where people don't know about new possibilities, or even if they know, haven't integrated them into their workflows or daily activities. The provocation creates a window to study how people can include technology in meaningful ways—not just how they'll use it, but how they'll create value through the new interaction.

My Journey: From Fine Arts to Fortune 500 Strategy

My background is in industrial design under the tradition of fine arts—a foundation that expanded my mindset from purely logical and mathematical perspectives to more perceptual and subjective analysis, where aesthetics and multiple points of view are valid sources of inspiration. However, I've always been drawn to complexity. I enjoy navigating uncertainty in complex systems.

This led me to approach a biomedical engineering school while still an undergraduate student. I worked with them for nearly ten years in academic and industry-applied research, designing biomedical equipment. My role was providing the "product" approach—expanding the functional mindset of engineers by incorporating user-centered design with product variables to make designs not only appealing but adapted to medical contexts.

Under this expanding scope, my school's focus shifted from "Industrial Design" to simply "Design." The Institute of Design at Illinois Institute of Technology embodied this transformation—the largest graduate design school in the United States and the first to open a PhD program in Design. After years working alongside biomedical engineers with international PhDs, I wanted to learn the same rigor and connection with industry that they had.

The Shift from Small Design to Big Design

My master's program emphasized strategy and business—similar to an MBA. I was mind-blown by the scope, relevance, and infrastructure of design consultancy in the US: multimillion-dollar projects with high relevance in corporations. I shifted—or better said, complemented—my formation in fine arts with structured ways to design with people and stakeholders, empowering everyone around the project while navigating innovation in corporate settings. This experience, from small research-funded projects in Colombia to multimillion-dollar projects in corporate America, was life-changing. I experienced what Tim Brown, former CEO of IDEO, calls the shift from "small design" to "big design."

My experience in the master's program connected directly with real companies and real projects. I spent my summer working with Lancaster General Health, designing remote monitoring systems for critical patients—an opportunity to apply my learnings in high-stakes healthcare contexts.

I continued to my PhD under the guidance of Professor Tom MacTavish, former director of Motorola Interaction Labs—a mentor who embodied the balance of academia and industry experience I was seeking. My doctoral research was not structured to generate academic results in isolation or to learn how to be a professor. From its inception, it was designed to generate new knowledge for industry, rooted in my experience working with multiple corporations, government agencies, and teaching—evidence of how to navigate new product innovation in corporate settings.

The Research Problem: Navigating Early Ambiguity

My experience in biomedical engineering and industrial design was challenged when I explored the notion of early prototyping—provocations—even when the variables of a project are not well defined, when the nature of the problem is so complex and ambiguous that it makes people uncomfortable.

Provocations (or "provotyping" in academic terms) wasn't a new concept, but it hadn't evolved in a structured way to become part of day-to-day processes in companies. My research explored the early inclusion of this method and collected emerging patterns from a diverse set of projects across different industries—generating models and heuristics that can help design researchers navigate early uncertainty in projects.

Research Outcomes

The doctoral research produced three primary deliverables applicable across industries—frameworks designed not for academic citation but for practical application in corporate innovation:

- Structured Provocation Model — A framework distinguishing provotypes from traditional design approaches, helping teams choose the right prototyping strategy for each innovation stage

- Provotyping Heuristics — Ten actionable principles for implementing the methodology in diverse organizational contexts

- Mixed Methods Application of Behavioral Theory (SDT) — Demonstrated how Self-Determination Theory can guide design decisions with measurable outcomes, bridging behavioral science and UX practice

My balance of creativity and abstract thinking from fine arts studies provides a counterweight to the rigor of doctoral research and the structure of strategy in corporate settings. Sometimes creativity is key to creating provocations in early project stages; rigor and method follow to avoid researcher assumptions and collect clean data to share with stakeholders—showing what matters to people, not just what designers and executives assume.

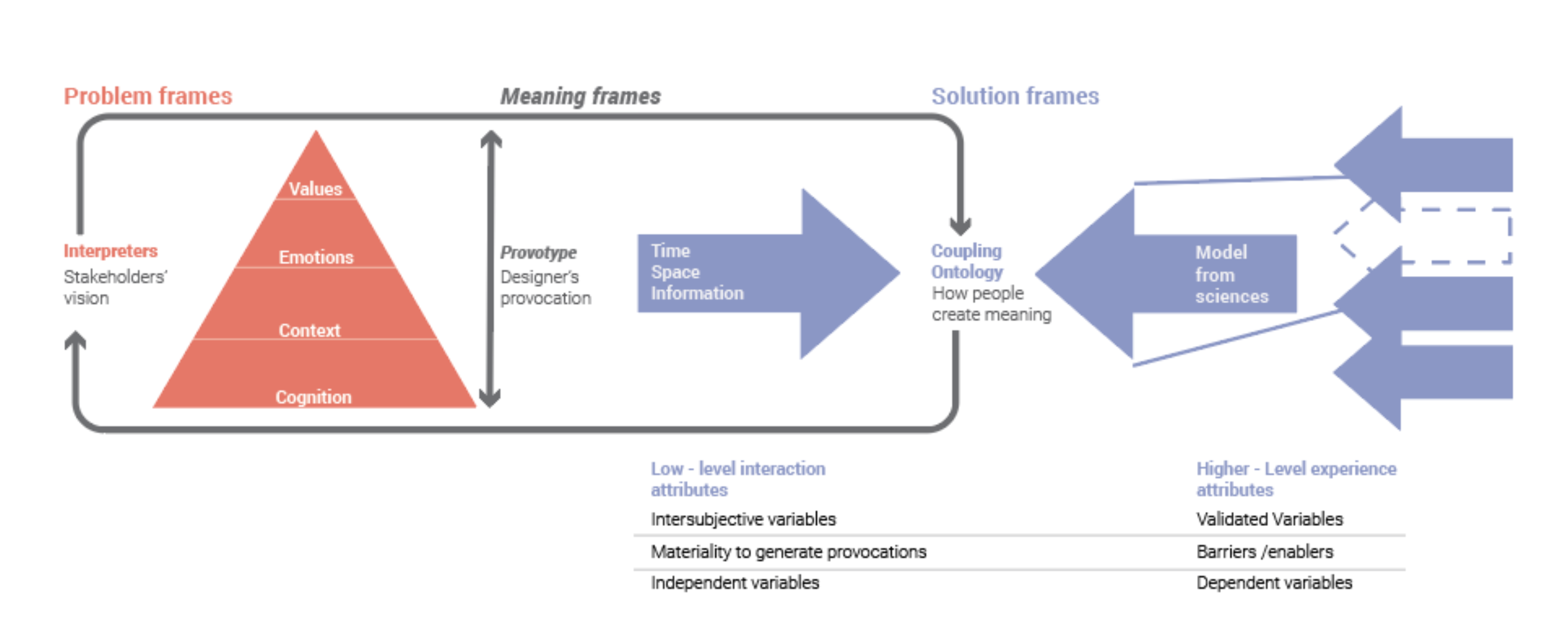

The Structured Provocation Model—mapping how provocations bridge problem framing and meaning creation in innovation projects

Provotyping Dimensions: A Strategic Comparison

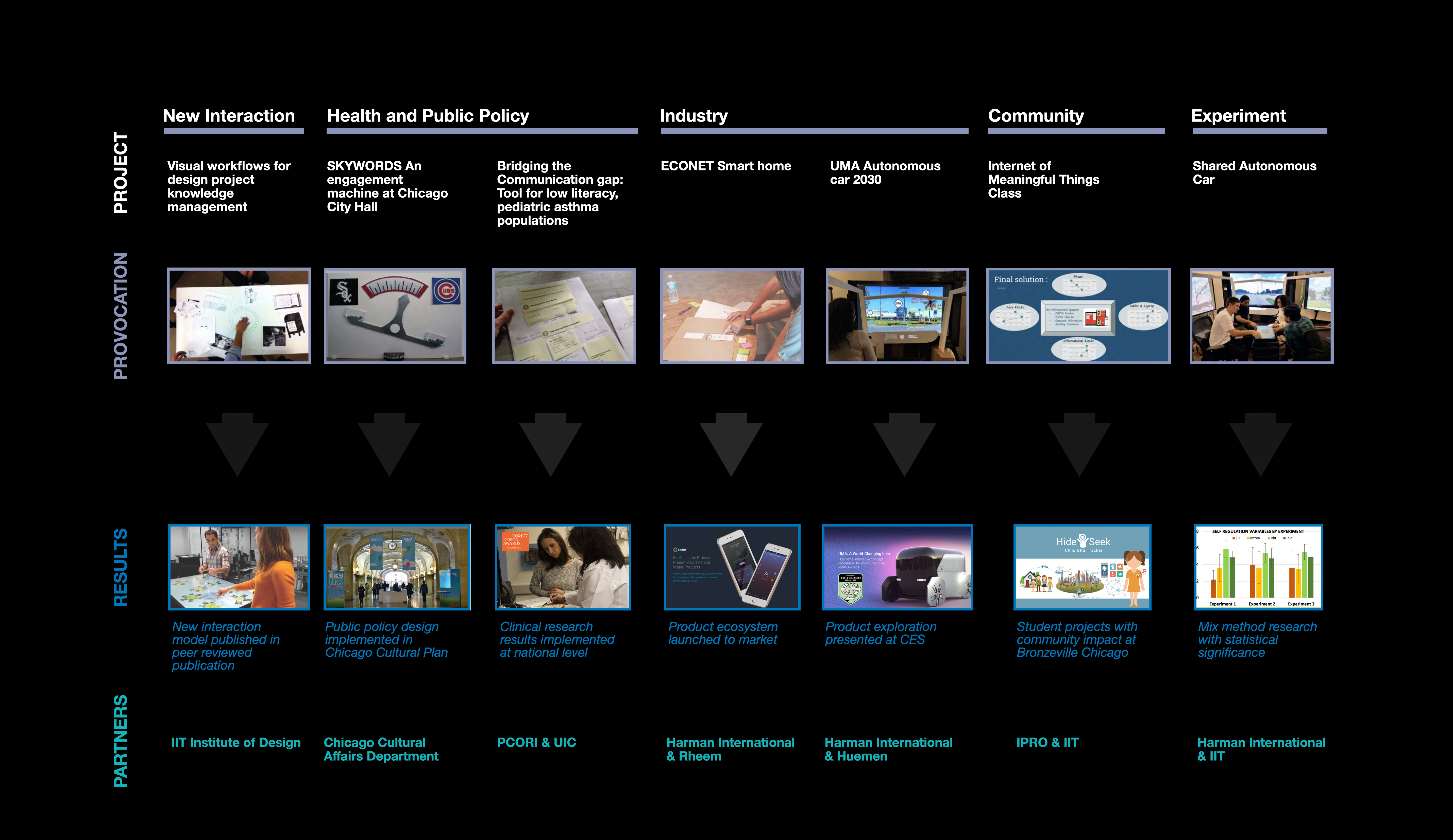

Through 6 case studies across healthcare, automotive, smart home, public policy, and educational settings, I developed a systematic framework distinguishing provotypes from traditional design approaches. This comparison became a core consulting deliverable for cross-functional alignment—helping stakeholders understand when to use which approach.

| Dimension | Provotypes | Design Thinking Prototypes | Industry Prototypes |

|---|---|---|---|

| When to use | Early stages | Middle of process | End of process |

| Intention of data | Unveil assumptions | Explore ideas | Validate solutions |

| How to use | Challenge beliefs | Build agreement | Refine details |

| Process focus | Meaning frames | Problem frames | Solution implementation |

| Designer's mindset | Defiance | Collaborative | Authoritative |

| Designer's role | Provocateur / Unveiler | Facilitator | Industry expert |

| Timeframe | Long-term / Mid-term | Mid-term / Short-term | Short-term |

| Main challenges | Suspension of disbelief | Ambiguity | Clear/unequivocal |

| Approach | Stakeholder-centered | User-centered | Expert-centered |

| Core concept | Transcendence | Tradition | Veracity |

Why This Framework Matters

In cross-functional innovation teams, stakeholders often talk past each other because they're using prototypes for different purposes. Engineering wants validation. Design wants exploration. Strategy wants assumption-testing. Meanwhile, users haven't yet imagined how new technology could fit into their lives. This framework provides shared vocabulary for deciding which approach fits which moment—preventing expensive misalignment before it happens and creating space for people to discover meaningful possibilities.

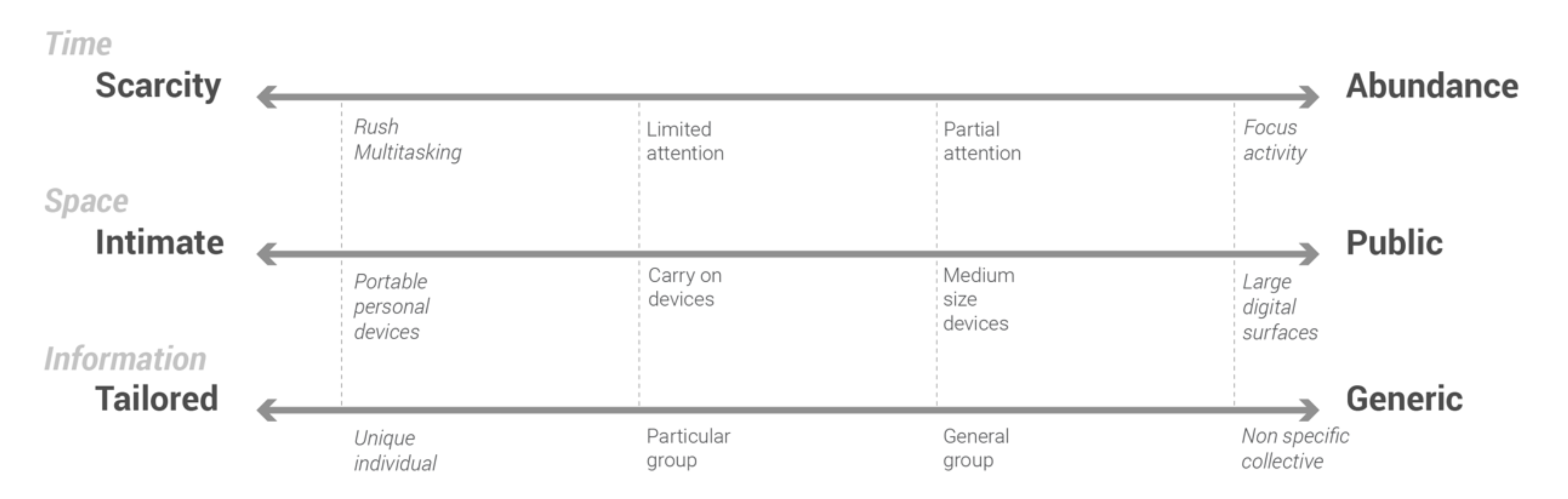

The Provotyping Tool—three interaction attributes (Time, Space, Information) as structured continua for designing provocations that challenge assumptions

Three Interaction Attributes for Structured Provocation

Beyond the framework, I developed a practical tool for designing provotypes. Based on analysis of interaction design literature and validated across case studies, three attributes emerged as the primary dimensions for manipulating user experience:

1. Time: Scarcity ↔ Abundance

How much time does the user have to interact? Rushed decisions reveal different needs than leisurely exploration. Provotypes can compress or expand time to test how urgency affects behavior and preference.

2. Space: Intimate ↔ Public

Is the interaction private or shared? Personal devices create different dynamics than public displays. Provotypes can manipulate spatial configuration to understand how privacy affects engagement and motivation.

3. Information: Tailored ↔ Generic

Is content personalized or universal? Tailored information creates connection but raises privacy concerns. Generic information feels safer but less engaging. Provotypes explore this continuum to find the right balance.

These three attributes became controlled variables in experimental research—proving that design decisions have measurable psychological effects. When you change spatial configuration (intimate vs. public), you measurably change motivation quality. This bridges the gap between intuitive design decisions and evidence-based practice.

Six Case Studies + One Teaching Application

The methodology was developed and tested across diverse contexts that reflect my career trajectory—from NIH-funded clinical research (building on my biomedical engineering background) to Fortune 500 product launches to civic engagement installations. Each case study contributed unique insights while validating the core framework, demonstrating how provotyping helps people discover meaningful relationships with unfamiliar technologies.

SkyWords: Civic Engagement Machine at Chicago City Hall

When governments make new policies, they often have limited methods for engaging the public. SkyWords was a site-specific installation—an "engagement machine"—installed on the ground floor of Chicago City Hall for ten days. The project used playful technology and the universal appeal of interaction to give voice to constituents typically excluded from policy decisions, challenging assumptions about how citizens want to participate in democracy.

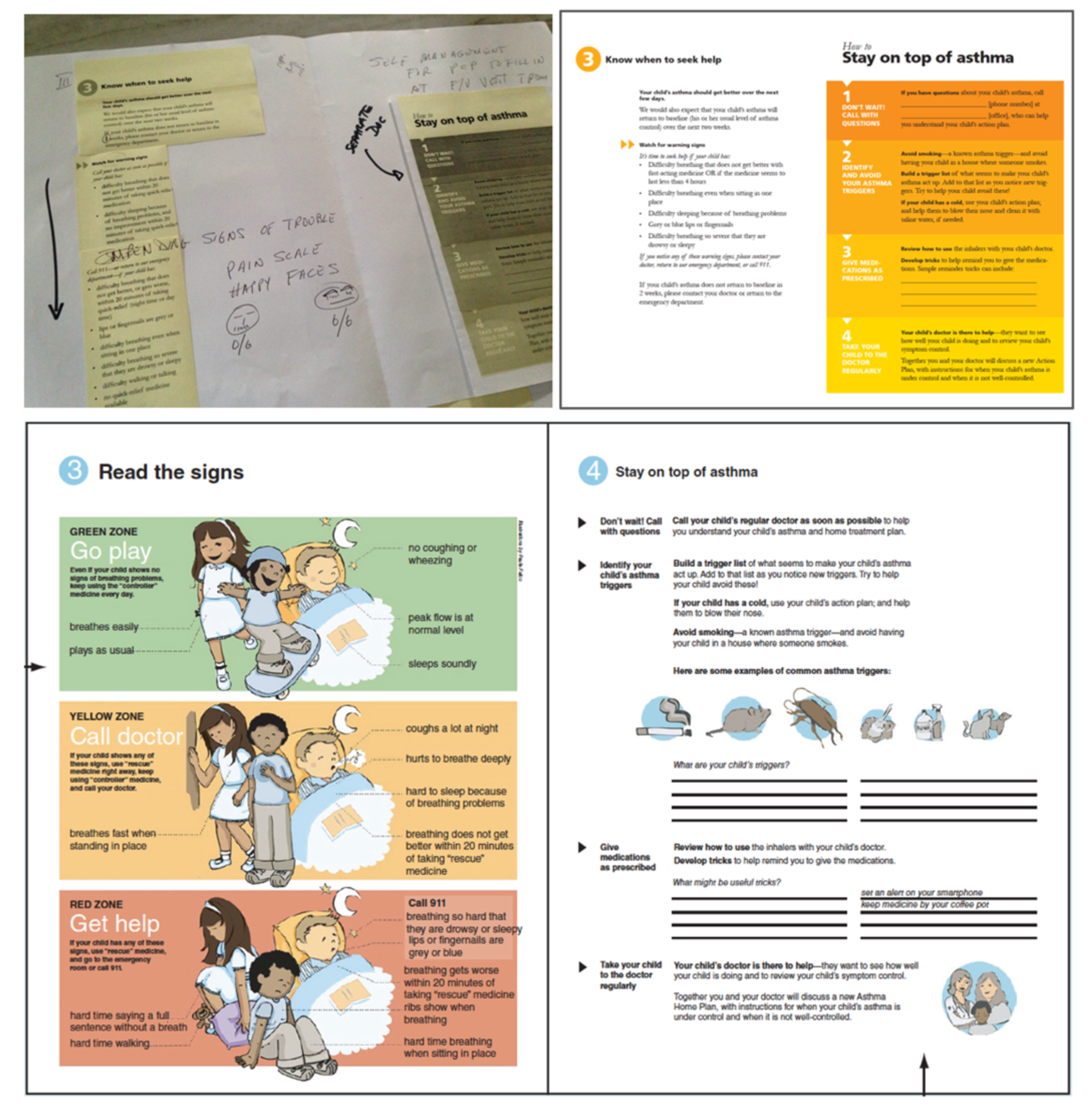

CHICAGO Trial: Pediatric Asthma Discharge Redesign

This NIH/PCORI-funded study across 6 Chicago hospitals tackled a deadly disparity: African American children in Chicago are 8 times more likely to die from asthma than white counterparts. Provotypes revealed that the ER discharge moment was perceived as too stressful for information retention—completely reframing the design challenge. Rather than better pamphlets, families needed multiple touchpoints with tailored, visual information.

Visual Workflows: Collaborative Design Knowledge Management

Research into replacing the one-device-per-person paradigm with shared digital surfaces for collaborative design analysis. Using an interactive table, we explored how designers might use digital space as an alternative for analyzing data collaboratively—with multi-gesture navigation and multiple users sharing one device. The study revealed how spatial proximity affects knowledge sharing behavior and decision-making in design teams.

Rheem Smart Home Ecosystem: Information for Meaningful Interactions

A corporate research effort for a 100-year-old appliance manufacturer facing the IoT revolution. The main challenge: unify diverse internal perspectives about what users actually need from connected water heaters and AC systems. Provotypes explored what data families find meaningful for energy/water savings—revealing the "Nonchalant" user who "just wants to shower" and doesn't want optimization.

UMA: Urban Mobility Assistant — Autonomous Car for 2030

An internal Harman/Samsung project envisioning Level 5 autonomous vehicle experiences for CES. Built a low-fidelity immersive lab with no budget—just methodological clarity and execution. Provotypes revealed that the challenge isn't the technology itself—it's designing the transition from "driver culture" to autonomous passengers.

Mixed Methods Experiment: Proxemics & Motivation for Behavior Change

A controlled experiment testing how spatial interaction design influences motivation for long-term behavior change. Three prototype conditions (personal/intimate, group/social, public/voice) were tested with Self-Determination Theory questionnaires. The study proved that design researchers can manipulate interaction attributes as controlled variables to test behavioral theories.

IPRO: Internet of Meaningful Things

Taught the provotyping methodology to interdisciplinary student teams at Illinois Institute of Technology through the Interprofessional Projects (IPRO) program. Students applied the framework to design meaningful IoT systems with real impact in Chicago communities—demonstrating that the methodology transfers beyond expert practitioners to emerging designers.

SkyWords installation at Chicago City Hall—using playful technology to challenge assumptions about civic participation

CHICAGO Trial materials—provotypes revealed that discharge moment stress prevented information retention, reframing the entire design challenge

Visual Workflows research—exploring how shared digital surfaces change collaborative decision-making behavior

Rheem research—low-fidelity provocations revealed four behavioral personas including the paradigm-shifting "Nonchalant" user

Autonomous vehicle lab—built with no budget using projectors, foamboard, and edited visualizations to create immersive experiences

IPRO class—teaching provotyping methodology to interdisciplinary student teams for real community impact

Statistical Validation: Proving Design Decisions Have Measurable Effects

While the methodology was developed through qualitative case studies, the final validation stage applied quantitative rigor. I designed a controlled experiment adapting Self-Determination Theory (SDT) to measure how different interaction models affect motivation for long-term behavior change.

Experimental Design

Research Question: How does spatial interaction design influence motivation quality?

- Independent Variable: Proxemics manipulated through three prototype conditions

- Prototype A: Personal/Intimate — Individual phone screens, private decisions

- Prototype B: Group/Social — Collaborative touchscreen, shared decisions

- Prototype C: Public — Immersive screens + voice control, collective decisions

- Dependent Variables: Self-Determination Theory motivation regulations (external, introjected, identified, integrated)

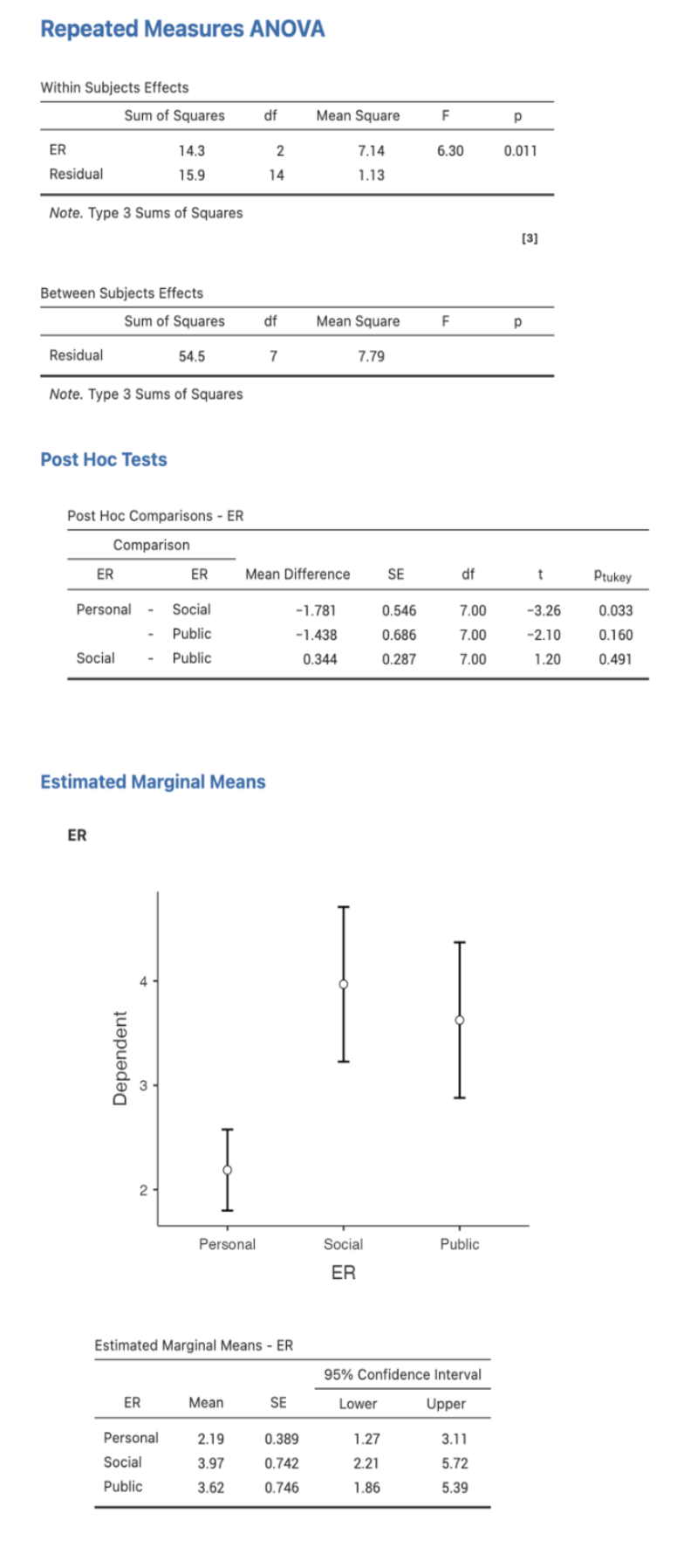

- Method: Repeated measures ANOVA + semi-structured interviews (n=8 groups)

Three experimental conditions—manipulating proxemics from personal to public space to measure motivation impact

Repeated measures ANOVA results—statistical evidence that spatial design affects motivation quality

What This Means for Practice

Participants felt significantly less externally regulated (motivated by rewards/punishments) in the personal/intimate condition compared to social condition. Private interactions increased perceived autonomy and shifted motivation toward more self-determined engagement—critical for long-term behavior change sustainability and technology adoption.

This matters especially now, with the rise of AI: the main problem is becoming adoption after the novelty and hype. Understanding motivation and cultural values is the key to designing technology that people feel connected to—finding positive meaning each time they use it, rather than abandoning it once the initial excitement fades.

The Methodological Contribution

This experiment proved that interaction design attributes can function as controlled independent variables to test behavioral theories. By manipulating spatial design (personal/social/public) while measuring motivation quality, I bridged the gap between design research and experimental psychology—showing that UX decisions have measurable psychological effects that can be studied with scientific rigor. This is the balance of creativity and rigor that I bring to every project.

Ten Heuristics for Structured Provotyping

The research culminated in actionable principles that guide practitioners implementing provotyping in their own innovation projects. These heuristics emerged from pattern analysis across all case studies and were validated through the controlled experiment.

Provotyping heuristics organized into implementation categories—actionable principles for innovation teams

Peer-Reviewed Publications

The Bottom Line

This isn't academic theory disconnected from industry—it's a consulting-ready framework developed inside Fortune 500 innovation projects and validated through peer-reviewed research. Products launched to market. Awards won. Statistical significance achieved. Methodology taught and transferred.

When your next innovation project needs to help people discover meaningful relationships with technology they haven't yet imagined using, provotyping provides the structured approach to de-risk the investment—aligning stakeholders, surfacing assumptions, and creating the conditions for products and services that people genuinely love.

My professional journey—from fine arts to biomedical engineering to Fortune 500 strategy—has prepared me to navigate complexity and ambiguity safely, empowering teams and clients to feel comfortable with uncertainty that leads to breakthrough innovation.

Reflection: Designer, Researcher, Strategist

My doctoral research is embedded in complexity, ambiguity, and corporate environment. It was designed to align stakeholders while giving entire teams better understanding of what's relevant to people—before pushing new technology that users still don't understand and can't integrate into the way they work or live.

I communicate this work from a strategy perspective: as a designer, researcher, and strategist who has worked closely with industry and stakeholders, who designs projects and research with knowledge of budget and return on investment, who understands the portfolio design of a company and the day-to-day challenges of a consultancy.

"Reality is not disciplinary—problems don't have professional labels. My knowledge only makes sense in the way I can empower my team and work together navigating ambiguity and complexity in a safe way, sharing this feeling with clients and making them comfortable with projects that begin with high uncertainty but end with products and services that people love and use repeatedly."

The Capability I Offer

I'm a leader in my field who can expand the capabilities of a business—selling rigor, method, and research to generate products with meaning. Products and services that explore new technologies while understanding how people feel and can be motivated to be better in their work environments or daily activities.

My professional journey has been diverse: understanding design from multiple perspectives and traditions, from fine arts intuition to engineering rigor, from small research-funded projects to multimillion-dollar corporate innovation. This diversity isn't fragmentation—it's integration. Moving fluidly between rapid qualitative insights for product iteration, rigorous quantitative validation when strategic decisions need statistical confidence, and mixed methods integration when neither tradition alone suffices.

What I've Learned

- Start corporate partnerships early — The richest insights came from embedded industry work, not isolated academic studies

- Creativity and rigor aren't opposites — Sometimes creativity is essential to create provocations; rigor follows to collect clean data

- Methodology must be transferable — Frameworks that can't be taught have limited impact

- Empower stakeholders, don't present to them — The opposite of rejection is ownership; when people participate, they own the revelations

What I'm Most Proud Of

Not the awards or publications—though those validate the work. I'm proud of being able to navigate ambiguity and complexity safely, making clients comfortable with projects that start uncertain but generate the best outcomes.

The thinking tools that outlast the researcher:

- The Provotyping Dimensions Table that helps teams choose the right approach

- The Time/Space/Information tool that structures assumption-testing

- The 10 Heuristics that guide practitioners without requiring expertise

- The students who now apply this methodology in their own careers

Frameworks don't disappear when the researcher leaves. They become part of how organizations think.